Estimated reading time: 17-19 minutes

As discussed in the previous two chapters, major historical events in Canada and around the world have shaped the country’s charitable giving landscape. This chapter examines where the sector stands today.

Overview of current charitable sector

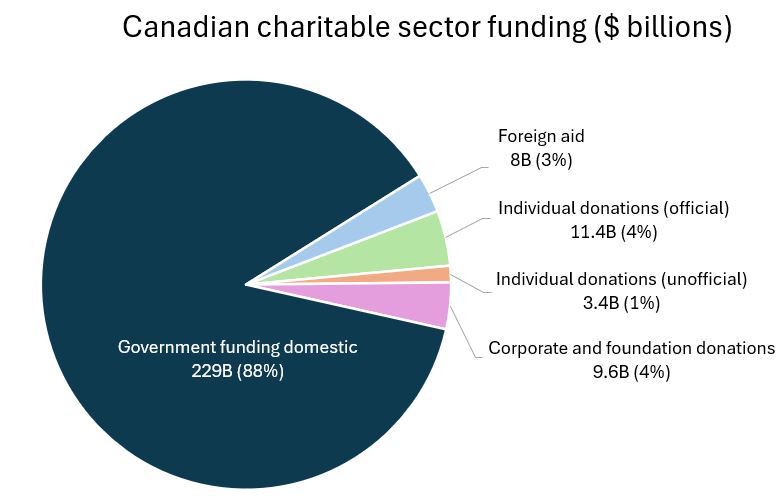

As I included in the introduction, the total of what I consider the Canadian charitable sector is over $261 billion (CAD). This includes $11.4 billion in private donations to charities (official donations from tax filings) [1], an estimated $3.4 billion in unofficial donations[2], $9.6 billion of corporation and foundation donations to charities[3], $229 billion of government funding to domestic charities[4], and roughly $8 billion of government foreign aid[5]. Some of these figures are from different years, since not all data is available each year, but this is just to give us an overall sense of scale.

This $261 billion charitable sector makes up 11% of Canada’s GDP.

In this chapter, I will dive into each of the above categories and provide more information about where this funding is coming from and where it’s going.

First though, let’s take a closer look at the domestic charities in Canada that receive the majority of this funding. Canada currently has 85,955 registered charities[6], employing 11% of the country’s full-time workforce[7] – more than the entire construction workforce (6.5%), or manufacturing workforce (8.7%)[8]. This marks a significant shift from the days when religious orders dominated the charitable landscape. Today, the sector is highly professionalized and a vital part of Canada’s economy.

Let’s take a moment to clarify what exactly allows a Canadian organization to call themselves a registered charity. As noted in the introduction, a charity is a legal entity registered with the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) that must meet specific requirements. These include operating as a non-profit, providing clear and tangible public benefits, and having ‘charitable purposes.’ These purposes must fall within one of four broad categories: (1) relief of poverty, (2) advancement of education, (3) advancement of religion, or (4) other benefits to the community deemed charitable by the courts, such as health promotion, environmental protection, amateur sports, and social services.[9].

While all charities are non-profits, not all non-profits are charities. Both enjoy tax-free status, but non-profits do not need to have charitable purposes and can be established for other activities, such as recreational sports. Unlike charities, they cannot issue tax receipts and do not register with the CRA, though they must follow non-profit regulations based on their provincial or federal incorporation. I don’t believe this distinction is well understood by the general population but is crucial to making informed donation decisions.

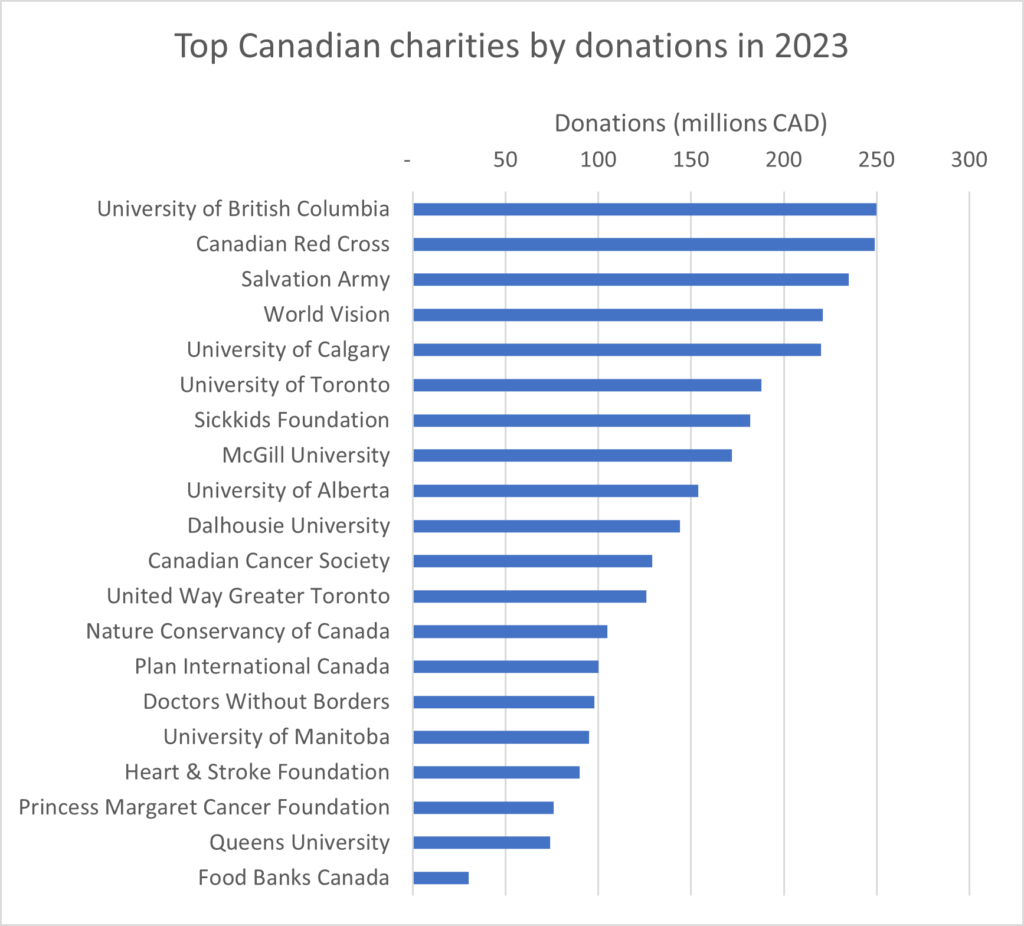

Now that we have a clearer understanding of what defines a charity, which charity do you think receives the most funding in Canada? Many might guess well-known names like United Way, World Vision, or the Canadian Red Cross. However, in 2023, the top recipient of donations was the University of British Columbia, which received $250 million[10]. In fact, six universities ranked among the top 10 charities by total donations that year, collectively receiving $1.13 billion.

I found this somewhat surprising, as I had assumed universities were primarily funded by tuition and government grants. While this is largely true – 46% of university funding comes from the government and 29% from tuition – the remaining portion comes from various sources, including approximately 5% from donations[11]. As we explore this sector further, I hope we find more unexpected insights like this, which can reshape our perceptions and perhaps our personal donation strategies.

Apart from Universities, which other charities are highest in terms of donations? Here is a full list I’ve put together of the top 20 in 2023[12].

The dominance of universities and medical research charities on this list may suggest that wealthier donors are playing a large role in shaping these figures, as there is a prestige associated with supporting higher education and medical research (you may even get your name on a new building or wing). At the same time, six organizations on the list focus on poverty alleviation and humanitarian aid, reflecting some recognition among Canadians of the importance of addressing basic human needs both at home and abroad.

If you were to create a list of the top 20 charities deserving the most funding – those that would provide the greatest benefit to Canadians and the world – would it look like this one? While each of us has different values, I suspect most Canadians’ lists would differ significantly from the one above. I certainly see some charities here that wouldn’t make my own list of the highest-impact organizations. This suggests that the current donation incentive system does not prioritize the most effective charities.

The list above covers only four or five sectors of charitable work. Expanding it to include all 85,955 registered charities would reveal many other areas, including animal welfare, elderly care, cultural heritage, religious work, the arts, sports and recreation, and more. There are also some fascinating charities that you may not even know exist. Here are a few I found while scanning the CRA registry:

- The Donkey Sanctuary of Canada: providing lifelong homes to donkeys who are neglected or abused

- Wooden Boat Museum of Newfoundland and Labrador: preserving the local legacy of wooden boat building

- Magicana: an arts organization dedicated to the advancement of magic as a performing art

- Green Iglu: partnering with remote and Indigenous communities to build greenhouse infrastructure for food production

- Clowns Sans Frontières: bringing clowning internationally to help children who are victims of violence and poverty

- Pickleball Canada: supporting pickleball players across Canada

- Freedom Trails Therapeutic Riding Association: dedicated to improving the quality of life for people with a disability through therapeutic horseback riding

The charitable sector in Canada is large and diverse, raising many difficult questions about how to make donation decisions – “The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind.”

Government funding to domestic charities

Let’s next examine the current government support which Canadian charities receive. As noted earlier, charities receive $229 billion in government funding annually – accounting for 69% of their total revenue and serving as a crucial funding source.

This funding comes from federal, provincial, and municipal governments. Federally, it is distributed through departments and programs such as Global Affairs Canada, the Canada Council for the Arts, Health Canada, and others. Provinces also offer various funding programs – for example, in Ontario, the Ontario Trillium Foundation supports community projects, the Ministry of Health funds local healthcare organizations, and the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks supports conservation initiatives.

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly how much of the $229 billion comes from each of the federal, provincial, and municipal levels, and it will vary by province. However, key sectors receiving these funds include healthcare, education, and social services. Hospitals alone receive approximately $90 billion annually[13], primarily from provincial funding. Universities receive around $20 billion per year[14], also through provincial funding. In social services, initiatives like the federal National Housing Strategy – a 10+ year, $115 billion program – help fund charities focused on affordable housing and homelessness.

Charities’ reliance on government funding has both advantages and drawbacks. On the positive side, it provides stability, increases capacity, and aligns charitable initiatives with public policy. However, this dependence can limit their independence, pressuring them to follow government priorities rather than their own assessments of need. It may also discourage risk-taking and innovation. Given these realities, understanding a charity’s level of government funding will be a key factor when we assess whether it’s a good choice for our donations.

Government funding to foreign aid

Moving from domestic to international, let’s now consider Canada’s foreign aid spending. This is important since understanding where the government allocates aid can later help us identify funding gaps where private donations may have the greatest impact. It also provides us insights into how our tax dollars are spent and the image Canada projects on the international stage.

Canada’s annual foreign aid spending fluctuates around $8 billion, or around $200 per capita. For reference, this compares to US foreign aid spending of $102 billion, or $300 per capita – 50% more[15]. As the world’s largest foreign aid donor, US funding decisions have significant global impact, making the recent USAID cutbacks particularly consequential.

We can also examine Canada’s foreign aid spending based on official development assistance (ODA), which we noted in the last chapter is the OECD’s standard method for measuring aid funding flows. This is often looked at in percentage of gross national income (GNI), and we remember that the Pearson Commission Report outlined a target rate of 0.7%.

Canada has never met the 0.7% target for ODA assistance. The closest it came was 0.53% in 1975, then steadily declined until 1999 when Canada gave only 0.25%. From 1999 to 2005, it increased back to 0.35%, motivated by the UN’s new Millenium Development Goals (MDGs), but since then, it has made little progress and has stagnated around the 0.3% mark, although recently reached 0.38% in 2023[16].

Compared to other G7 countries, Canada’s 0.38% contribution ranked it 5th in 2023. Canada was behind Germany (0.79%), the UK (0.51%), France (0.48%), and Japan (0.44%), and was only ahead of Italy (0.27%) and the US (0.24%). This positions Canada as a laggard, even though I think many people would assume Canada to be a leader in such efforts. The only other countries besides Germany that surpassed the 0.7% target were Denmark, Luxembourg, Norway, and Sweden.

The Canadian government has promised to increase Canada’s international assistance every year, yet in their 2023 budget, they actually reduced their foreign aid budget by 1.3 billion, or 15%[17]. Since then, they have recommitted to increasing it by $100-200 million per year, but it will take many years to return even to previous levels.

You may be wondering what types of aid are included in ODA. It includes assistance such as grants, debt relief, loans with favorable terms, humanitarian assistance, and technical assistance. Interestingly, it can also include assistance to refugees in the donor country for up to one year. Note that ODA does not include military aid, private investment, or export credits.

The ability to report on in-donor country refugee costs has been a controversial topic in recent years. Allowing countries to include these costs in their ODA reports incentivizes them to allocate more funding to domestic programs, diverting resources away from international aid efforts. Essentially, it amounts to payments from donor countries to themselves. While this has been an issue ever since the European migration crisis in 2014, the Ukraine war has driven these costs sharply higher to 14.4% of all ODA funding [18]. As Oxfam noted, an ‘obscene amount of aid is going back into the pockets of rich countries’[19]. Canada is also following this trend, with its reported domestic refugee spending increasing fivefold from 2020 to 2022[20].

When considering the funding that Canada actually sends internationally, let’s look at where it ends up. About 70% of this funding is distributed through Global Affairs Canada, with the majority provided bilaterally from country to country (although it’s still mainly channeled through multilateral organizations). The remaining amount directly funds multilateral organizations, such as the World Bank and the UN system[21]. So we can see here the importance of these multilateral organizations in terms of implementing Canada’s international programs. In terms of UN funding, Canada supports various UN organizations, with the largest contributions going to the World Food Programme ($449 million) and UNICEF ($355 million), and the smallest to the International Organization for Migration ($43 million).[22].

Geographically, Canada’s international aid ends up in a diverse set of countries. From April 2022 to May 2023, Canada funded programs in 49 countries, with the top countries being Nigeria, Ethiopia, Bangladesh, Tanzania, and Democratic Republic of the Congo[23]. I’ve excluded Ukraine here which received an exceptional loan of $4.85 billion during this period. Ethiopia and Bangladesh have both been in the top two funded countries since 2018.

Looking at humanitarian aid specifically, which is often considered the highest-impact work due to its life-saving nature, it usually accounts for only 8-13% of Canada’s total international assistance spending[24]. This may surprise some Canadians, as many associate Canada’s international aid primarily with humanitarian aid. For comparison, the US allocates 20-25% of its ODA funding to humanitarian aid, while countries like Türkiye regularly direct up to 90% to humanitarian efforts, so Canada is lagging behind in this as well[25].

Some may be equally surprised by the range of sectors that Canada’s international aid supports beyond humanitarian assistance. Recently, this has included: 16% of funding to the health sector, 6% to agriculture, forestry, and fishing, 8% to energy generation, distribution, and efficiency, 5% to education, 8% to government and civil society, and 6% to population policies and reproductive health, among others.

Looking at a few specific examples of activities included in these sectors, Canada has funded programs such as teacher training, medical research, COVID-19 control, tobacco use prevention, safe abortion services, STD control, local police and prison services, election support, fisheries development, livestock veterinary services, tourism policy development, and much more. The reality is that many people are unaware of how broad these international aid portfolios are. This issue is currently a hot-button topic in the US, where USAID’s portfolio is under heavy scrutiny regarding the types of programs it supports with taxpayer funds. I believe that overall, increased transparency in these activities would be valuable so citizens can better understand how their contributions are being used.

Another interesting thing about Canada’s foreign aid is its emphasis on gender equality. From 2021-2022 year, Canada committed $4 billion, or 77% of its bilateral aid, to gender equality initiatives, which is much greater than the 43% DAC average. This is propelled by Canada’s Feminist Humanitarian Assistance Policy, which was launched by Prime Minister Trudeau’s government in 2017[26].

Individual donations: how Canadians give

Let’s shifting focus to now better understand individual donations from Canadian citizens. We saw earlier that Canadians contribute $11.4 billion annually in official donations, along with another $3.4 billion in unofficial donations. These figures position Canada as one of the more generous countries globally. According to the World Giving Index, which ranks countries based on citizens’ generosity through donations and volunteering, Canada ranked 11th in its 2024 report. However, Canada has dropped from 8th place in 2023 and 3rd place in 2010[27].

Based on data from Canada Helps, a leading online platform for charitable donations in Canada, 60% of Canadians reported donating to charities in 2024[28]. This is also trending down, though, from 82% in 2013 and 85% in 2004[29]. In comparison, 69% of Americans gave financially to charity in 2023[30], contributing a total of $557 billion in private donations[31]. Therefore, on a per capita basis, Canadians donated $370 annually, while Americans donated a staggering $2,378. The US also ranked higher on the World Giving Index, at 6th place. So, despite Canadians’ reputation for generosity, Americans are giving far more. Looking globally, about one-third of people donate to charity.

While the above figures are based on various surveys, we can also analyze official CRA tax data. This data shows a similar downward trend in donations, as in 2022, only 17.1% of Canadians declared charitable donations, down from 25.7% in 1997[32].

The decrease in Canadian donors is primarily seen among younger generations, as there is a positive correlation between age and amount of charitable donations, with older generations donating more. For instance, only 39% of Canadians aged 18-24 donate financially, compared to 80% of those aged 70 and older[33]. While younger generations have historically donated the least, the recent amounts donated by them are even lower compared to similar generations in the past. There are likely many contributing factors, such as the high cost of living and student debt, but one factor that may disproportionately affect these younger generations is the reduction in religious influence. Fewer younger people are actively practicing religion, where the value of charitable giving has historically been taught.

Across all age groups, people who are religious are more likely to donate. In fact, 54% of all Canadian donors are actively involved in religious activities[34]. Another interesting demographic trend is that women tend to donate more than men. So, based on the full set of factors, the most likely person to donate in Canada would be a woman aged 35 or older, with higher education and income, and who is religiously active.

Donor behavior can also be examined by income bracket. Interestingly, the largest proportion of donations comes from the lowest 20% of income earners, who donate 2.1% of their total household income, compared to the highest income earners who donate only 0.4%[35]. We know the old saying, “the poor help the poor; the rich help themselves”, which appears to be true in Canada to some extent.

Now that we understand more about Canadian donors, let’s explore where they are sending their donations. When it comes to the sectors Canadians donate to, the top areas are health, with 55% of donors supporting it; social services, with 40% of donors; and animal charities, with 27% of donors[36]. Regarding religious causes, 21% of donors contribute to them. Education receives support from only 14% of donors, which is interesting considering the substantial funding universities receive, as we saw earlier.

While we don’t have precise data on how many donations go internationally versus domestically, we do know that 17% of Canadian donors indicated that they support international initiatives. This suggests that the remaining majority focus on local causes within Canada[37].

One important funding flow that does go internationally from private individuals is diaspora remittances. These are funds sent by migrants living in Canada back to their home countries, usually to support family members. While not considered charitable giving, remittances can serve as a major income source for households in certain low-income countries. In some countries, remittances account for nearly 6% of their GDP[38]. Globally, annual remittances are estimated at $831 billion[39], almost four times the total global ODA of $211 billion. In Canada, total remittances are estimated at $12 billion – 50% more than Canada’s entire foreign aid spending[40]. This highlights an important lesson – one we’ll revisit – that international aid represents only a small part of how people in need around the world meet their basic requirements.

Corporate giving and foundations

Finally, corporate and philanthropic foundation donations also bolster the charitable sector in Canada. Corporate donations are contributions made by businesses to charities (perhaps you’ve been part of a company-led United Way donation campaign). With the rise of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), where businesses integrate social concerns into their operations, corporate donations have increased over the past two decades. Although data on these donations in Canada is limited, the total annual donations could reach into the low billions.

Foundations are organizations created to allocate assets for the public good, often established by corporations for charitable purposes. For example, the Mastercard Foundation in Toronto invests hundreds of millions annually in initiatives like COVID-19 response in Africa and Indigenous programs in Canada. While detailed data is scant on foundation donations in Canada, I’ve calculated that total corporate and foundation donations are approximately $9.6 billion annually. Globally, there are over 260,000 philanthropic foundations, with 60% in Europe and 35% in North America. Total assets exceed USD 1.5 trillion, with an average of 10% spent on programs each year[41]. Foundations are a major player in the world of philanthropy.

Okay, that was a lot of information, but it’s key to understanding the basics of Canada’s charitable sector and where the money flows. It’s a large and diverse sector that provides critical support for social development, both in Canada and abroad. But how well is all this funding spent, and are these initiatives really effective? Let’s explore in the next chapter.

[1] Figures are from 2022: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/240314/g-b001-eng.htm

[2] Calculated as 30% of official donations based on past surveys: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-25-0001/index-eng.htm

[3] Calculated using 2022 data from: https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/charities-giving/charities/about-charities-directorate/report-on-charities-program/report-on-charities-program-2022-2023.html

[4] Figures are from 2021: https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/charities-giving/charities/about-charities-directorate/report-on-charities-program/report-on-charities-program-2022-2023.html

[5] average of past 3 years with one-time exceptional grants removed – https://www.international.gc.ca/transparency-transparence/international-assistance-report-stat-rapport-aide-internationale/index.aspx?lang=eng

[6] https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/charities-giving/charities/about-charities-directorate/report-on-charities-program/report-on-charities-program-2022-2023.html

[7] https://www.canadahelps.org/en/the-giving-report/

[8] https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1410020201

[9] https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/charities-giving/charities/registering-charitable-qualified-donee-status/apply-become-registered-charity/establishing/what-charitable.html

[10] https://www.charityintelligence.ca/charity-details/43-university-of-british-columbia

[11] https://www.cmec.ca/299/Education_in_Canada__An_Overview.html#:~:text=Government%20funding%20is%20the%20largest,of%20total%20postsecondary%20education%20revenue

[12] Created using financial data from https://www.charityintelligence.ca/index.php. I may have missed some from this list.

[13] https://www.cma.ca/how-health-care-funded-canada

[14] https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/240723/dq240723a-eng.htm

[15] https://www.foreignassistance.gov/

[16] https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/net-oda.html

[17] https://www.mcleodgroup.ca/2023/03/promises-made-promises-broken-foreign-aid-and-budget-2023/

[18] https://oecd-development-matters.org/2023/05/11/the-elephant-in-the-room-in-donor-refugee-costs/

[19] https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/obscene-percent-aid-going-back-pockets-rich-countries

[20] https://www.international.gc.ca/transparency-transparence/international-assistance-report-stat-rapport-aide-internationale/index.aspx?lang=eng

[21] https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/aa7e3298-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/5e331623-en&_csp_=b14d4f60505d057b456dd1730d8fcea3&itemIGO=oecd&itemContentType=chapter

[23] https://www.international.gc.ca/transparency-transparence/international-assistance-report-stat-rapport-aide-internationale/2022-2023.aspx?lang=eng

[25] https://data-explorer.oecd.org/vis?df[ds]=DisseminateFinalBoost&df[id]=DSD_CRS%40DF_CRS&df[ag]=OECD.DCD.FSD&dq=GBR%2BCAN%2BUSA..700.100._T._T.D.Q._T..&lom=LASTNPERIODS&lo=5&to[TIME_PERIOD]=false&vw=tb

[26] https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/aa7e3298-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/5e331623-en&_csp_=b14d4f60505d057b456dd1730d8fcea3&itemIGO=oecd&itemContentType=chapter

[27] https://www.cafonline.org/insights/research/world-giving-index

[28] https://www.canadahelps.org/en/the-giving-report/

[29] https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-652-x/89-652-x2015008-eng.htm

[30] https://nonprofitssource.com/online-giving-statistics/#:~:text=By%20the%20end%20of%20last,a%20regular%20basis%20(69%25).

[31] https://www.bwf.com/giving-usa-2024-report-insights/#:~:text=Human%20Services%20giving%20narrowly%20surpasse,previous%20high%20of%20%2488.70%20billion

[32] https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/240314/dq240314b-eng.htm

[33] https://www.canadahelps.org/en/the-giving-report/

[34] https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-652-x/89-652-x2015008-eng.htm

[35] Ibid

[36] Ibid

[37] https://www.canadahelps.org/en/the-giving-report/?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQiAwtu9BhC8ARIsAI9JHakb7xGXXGFgervQoh30WirLKp9T-W59gw9s-q_syo9qfsoAGu9LqhQaAq_jEALw_wcB&gclsrc=aw.ds

[38] https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/Series/Back-to-Basics/Remittances#:~:text=Remittance%20flows%20to%20low%2Dincome,GDP%20for%20middle%2Dincome%20countries.

[39] https://worldmigrationreport.iom.int/what-we-do/world-migration-report-2024-chapter-2/international-remittances#:~:text=Migrants%20sent%20an%20estimated%20USD,USD%20717%20billion%20in%202020.

[40] https://truenorthwire.com/2024/12/immigrants-in-canada-sent-12-billion-worth-of-remittances-abroad-in-2023/

[41] https://www.hks.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/2023-09/global_philanthropy_report_final_april_2018.pdf

Lots of great info to process here but I wouldn’t be alone in highlighting this statistic: “Canadians donated $370 annually, while Americans donated a staggering $2,378.” Would be interesting to know what would account for that disparity? It’s not that $2,378 is high – that would be well below 5% of an individual’s net income. It’s likely closer to 2%. And obviously well below the Biblical teaching to tithe (10%) The “staggering” aspect of this stat is how little Canadians give. Clearly the values of Canadians individuals has changed. What would it have been two generations ago. Or even one? Could be a result of the shift away from Christian teaching. That would also make for some interesting research.

Indeed, when measured as a percentage of gross income, Americans donate 2.1% while Canadians give only 0.65%. Based on this, Americans donate about 3.2 times Canadians. It would be interesting to investigate this difference and how trends have evolved over time – perhaps a topic for a future chapter!

Lots of info here but still hoping you will expand some details on the amount of money paid to CEOs of charities! and the % of monies collected. When I looked at online details of CEO salaries it made us re think where our donations go.

Staff salaries, including CEO salaries, is an interesting topic. I will have a look at this in a few weeks, when I plan to start talking about charity effectiveness and what to consider when selecting charities for donations. Thanks for reading.