Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

Motivation for writing this blog

Canadians donate billions of dollars to charities each year, yet rarely conduct the research required to understand if their donation will be used effectively. For those that put in the effort to try and inform their donations, the information out there can be difficult to understand, and in some cases misleading. In fact, many of the metrics we use to judge a ‘good’ charity – like low administrative costs – have little to do with actual impact. This blog is about rethinking how we give, so that generosity actually leads to meaningful change.

Let me introduce myself! I’m Taylor Raeburn-Gibson, a Canadian from Ontario with a diverse background spanning the Canadian military, private sector, and humanitarian aid. Over the past four years, I’ve worked for a United Nations organization on shelter and settlements projects, focusing on supporting those affected by conflicts and disasters. My experience has also included volunteering with charities across Canada, from homeless shelters and refugee support centres to religious community service. These opportunities have given me a unique perspective on the complexities of both local and global aid efforts.

In light of my recent work, people close to me have often asked where they should donate money – whether to the UN organization I work for or if I’d recommend a different organization. It’s a simple question, but I quickly realized that answering it properly requires far more thoughtfulness than I had anticipated. While there is lots of information online, including various rankings, this information is unreliable and can be misleading. To truly address this question, we must consider which organization will do the most good with my money. And to determine this requires defining what “good” actually means. This realization led me down a rabbit hole of research – one that I hope to unpack in this blog.

Effective giving is not an easy endeavor, and many thought leaders on this subject acknowledge its difficulty. Elon Musk, a less traditional philanthropist, has said “It is very hard to donate money if you [care] about it doing actual good, not merely the appearance of it.” His observation highlights that charitable giving is challenged not only by the extreme difficulty of ensuring impact, but also by our human tendency to seek recognition for our good deeds. These difficult questions are exactly what this blog will explore.

So in response to those who have asked me about donation recommendations, I present this blog as my response! The truth is, there’s no simple answer – but that’s exactly why this conversation matters. It will take a series of deep dives to truly unpack the complexities of charitable impact and get to the heart of what makes giving effective.

This blog will explore the many facets of charitable giving, with a focus on issues that impact Canada and Canadians. By the end of this series, I hope we’ll be better equipped to become informed, effective donors who can engage more meaningfully with charities. The insights we gain may also help us become better volunteers and advocates for change, both locally and globally.

When I first mentioned the idea for this blog to my wife, she asked, “Who’s going to read that?”. The answer is, I’m not quite sure who the audience will be, but I hope it will resonate with anyone who cares about charitable giving and wants to ensure their donations have real impact. I’m also writing this blog to figure it out myself as much as to share what I learn with you.

This blog is meant for people who already want to donate financially – it’s not meant to convince others on the merits of donating. But if this somehow inspires people to donate more, then I think that would be a great consequence. Canadians are unfortunately donating less and less these days, despite living in one of the world’s wealthier nations. The average Canadian household income in the top 17% of global income earners[1]. Additionally, Canada’s Gross National Income (GNI) per capita (average income per person) is $54,040 USD. This is 246x the GNI per capita in Burundi, the country with the lowest GNI[2]. Given the wealth of Canadians, there’s significant potential for Canadians to make a meaningful impact globally.

My goal is to write this blog in a way that makes the many complexities of the charitable sector accessible to everyone. While I aim to keep things clear and approachable, I’ll back up my ideas with data and provide references along the way to ensure some level of academic rigor. As I write, I’ll also keep in mind Bob Dylan’s refrain, “Ah, but I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now”. I’ll aim to avoid writing with ‘youthful’ overconfidence, as I still lack the experience to grasp the full complexities of these topics.

Defining key terms

Before we proceed with the detailed content of the blog, I’d like to first define some basic terms I plan to use. Some of these may seem simple but are often misunderstood.

Starting at the highest level, the best overall term I can think of to encapsulate most of the topics I plan to review is charitable work or charitable giving. Within this is the idea of charity. Charity refers to acts of kindness or generosity intended to help those in need or to support a good cause. Thus, charitable work is an action done to help those in need and charitable giving is the provision of some type of support to a charitable end, such as money, goods, or volunteering. Charity originates from the Latin word caritas, meaning “affection”, or unconditional love. Over time, the word evolved through the French charité, becoming a central concept in the medieval Christian church.

Other terms are often used to describe charitable work, such as aid. While charity typically focuses on addressing immediate needs, aid has a broader scope. It encompasses both relief efforts, like those following disasters or conflicts, and development activities, such as improving long-term access to drinking water in water-scarce areas. Aid is also more systematic, as it is usually organized and delivered through planned and structured mechanisms, often involving governments.

The term aid is primarily used to describe assistance provided across international borders, commonly referred to as international aid or foreign aid. While these terms are often used interchangeably, international aid typically encompasses not only government assistance but also aid from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and the private sector. Foreign aid strictly refers to aid provided by one country’s government directly to another country (considered bilateral aid) or to a multilateral organization like the World Bank or WHO (considered multilateral aid).

While I am including foreign aid under this overall idea of charitable work, we will discuss about how foreign aid is not, in fact, truly charitable as it is mainly driven by strategic, political, or economic interests of the donor country. This has recently been exemplified by the Trump Administration’s pause on all foreign aid to refocus it on American national interests[3].

Finally, you may also see the term domestic aid, which can include various activities led by the government or large institutions (ie. Red Cross) in a home country, such as disaster relief or social service programs.

These various types of aid can be categorized by their purpose, including humanitarian aid, development aid, military aid, economic aid, and others. The two main types I will focus on are humanitarian aid and development aid. Humanitarian aid is typically provided in response to crises, such as natural disasters, conflicts, or epidemics, and usually includes food, water, shelter, medical care, and other essential services. In contrast, development aid aims at long-term improvements in economic, social, or governance sectors.

You will have also heard of the term philanthropy. The term philanthropy has the broadest scope but tends to focus on more long-term actions to address the root causes of social issues including advocacy efforts and strategic investment. Philanthropy also comes from Greek, which is a combination of “philos” (love), with “anthropos” (humanity). So literally meaning “love of humanity”, philanthropy has been used over the centuries to describe acts of kindness for our fellow humans.

I’d also like to define the terms charity, non-profit, and non-governmental organization (NGO). In Canada, a charity is a legal entity that must be registered with the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) and meet certain requirements (which will be discussed in a later chapter). A non-profit (or not-for-profit) organization in Canada does not need to register with the CRA, but it still must comply with non-profit regulations, depending on whether it is incorporated at the provincial or federal level. The term NGO in Canada typically refers to either charities or non-profits that operate independently from the government. However, an important distinction is that internationally, NGO is more broadly used to describe all charitable organizations working on various global issues such as poverty alleviation, climate change, human rights, or development. So, when researching international organizations, most will fall into this NGO category unless they are affiliated with a government or intergovernmental organization.

Scale of charitable giving in Canada

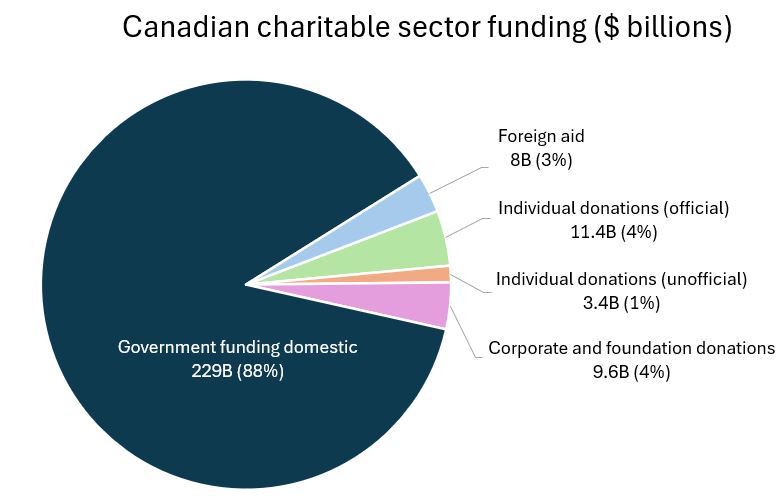

Now that we’ve clarified key definitions, let’s examine why they matter. When combined, the financial flows directed towards what I consider the Canadian charitable sector totals over $261 billion (CAD). This includes $11.4 billion in private donations (official donations from tax filings)[4], an estimated $3.4 billion in unofficial donations[5], $9.6 billion of corporation and foundation donations[6], $229 billion of government funding[7], and roughly $8 billion of government foreign aid[8]. You might notice that the government funding number is quite high, which is mainly due to the substantial support the government provides to Canadian hospitals (approx. $90 billion[9]) and universities (approx. $20 billion[10]). It’s a grey area if some of these should really be considered part of the charitable sector, since they really are public services paid for by taxes, but I include them here since Canada does consider them as charities.

Note that there are certain items I chose not to include such as remittances, which are gifts made to family members in other countries, and volunteer labour, which does have a monetized value.

So we are talking about big money here. Largely from your tax dollars, $5,725 annually per person is allocated to domestic charities and $200 annually per person to foreign aid. Then, considering the average personal donation to charities is another $370 per year, in total the average Canadian is contributing $6,295 per year to charities. That’s about 11% of the average Canadian’s earnings.

To put things further into perspective, this $261 billion charitable sector makes up a substantial portion of the Canadian economy – roughly 11% of GDP. If we deduct the figure for hospitals, which can be seen as a public service, the remaining $171 billion sector is larger than Canada’s entire energy sector[11]. While these numbers seem large, the real question is: how much impact is this funding actually generating? That’s the tough question we’ll seek to answer together.

Given the importance and size of the charitable sector in Canada, how many Canadians can speak knowledgeably about how charities operate in Canada? Despite its size similarity to the energy sector, why do we not treat the charitable sector with the same scrutiny and care? Considering the funding going into charities, do we have good data to confirm that they are being effective? These are questions I personally didn’t fully understand before researching for this blog, and I suspect many others may be in the same position. I plan to explore these topics in more detail in the coming months.

This blog will consist of a series of ‘chapters’, starting with some background on these topics including the history of how charitable activities have evolved in Canada. Then, I’ll explore the modern sector—how it’s structured, its effectiveness, and the challenges it currently faces. I’ll take time to review effective altruism, a recent movement closely tied with this subject. With this in place, I hope to analyze critically about how we can better inform ourselves to support charitable efforts more effectively. This is the plan for now, but it may evolve or expand organically over time. Thanks for reading!

[1] https://wid.world/income-comparator/

[2] https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD?most_recent_value_desc=false

[3] https://www.state.gov/implementing-the-presidents-executive-order-on-reevaluating-and-realigning-united-states-foreign-aid/

[4] Figures are from 2022: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/240314/g-b001-eng.htm

[5] Calculated as 30% of official donations based on past surveys: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-25-0001/index-eng.htm

[6] Calculated using 2022 data from: https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/charities-giving/charities/about-charities-directorate/report-on-charities-program/report-on-charities-program-2022-2023.html

[7] Figures are from 2021: https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/charities-giving/charities/about-charities-directorate/report-on-charities-program/report-on-charities-program-2022-2023.html

[8] Average of past 3 years with one-time exceptional grants removed – https://www.international.gc.ca/transparency-transparence/international-assistance-report-stat-rapport-aide-internationale/index.aspx?lang=eng

[9] https://www.cma.ca/how-health-care-funded-canada

[10] https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/240723/dq240723a-eng.htm

[11] https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610043402

We are just getting into this blog and look forward to further reading and research. A very worthy subject.

I feel like you wrote this just for me! Real looking forward to the next chapter (s)! Thanks!

Great info Taylor. We’ve already adjusted our giving habits. Looking forward to chapter two. Thank you!